|

|||||||||||||||

| The Vodafone Case & Tax Litigation in India – Practical Repercussions | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

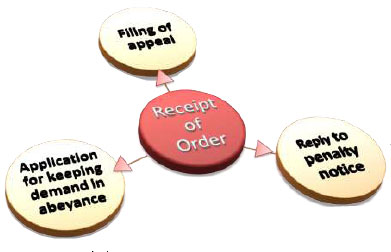

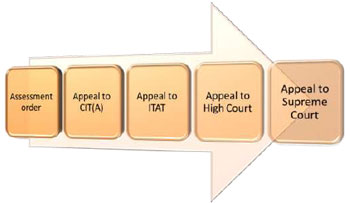

Having filed an appeal to the CIT(A), replied to the show cause notice for penalty and applied for keeping the demand in abeyance, the tax payer needs to be very vigilant as many times, the tax officers have been known to approach the tax payer’s bank and attach the bank account of the tax payer in order to enforce the recovery of the demand. This, of course, happens in extreme cases but the number of occurrences of such situations is fast increasing. As and when the appeal to the CIT(A) is fixed by the appellate officer for a hearing, the tax payer would need to prepare himself with a strong case and present the same to the officer. Generally, in the normal course, appeals to the CIT(A) take somewhere between 6 to 15 months to be heard. Even after the first hearing, the matter may drag on for a few days/weeks/months depending on the complexity of the matter. At a practical level, it has often happened that the matter is heard completely and before the appellate order is passed, the concerned officer gets transferred. In such a situation, the new officer would start afresh and hear the case once again. This would only delay the disposal of the appeal further. If the tax officer has been convinced to keep the demand or part thereof in abeyance, once the appellate order of the CIT(A) is received, if the same is against the tax payer and in favour of the Revenue, then surely, the tax officer will make every effort to recover the unpaid demand. It would be very difficult to get a stay on the demand once the first appeal is disposed off against the tax payer and in favour of the Revenue. Therefore, in such cases, the tax payer would need to make arrangements to pay off the unpaid demand immediately failing which, the tax department would not only take coercive action against the tax payer but also levy further interest for non payment of the demand. This would only add to the financial burden already being faced. Also, once the first level appellate order is received, the penalty order is also passed soon thereafter. Therefore, if the CIT(A) confirms the assessment order, then invariably, the penalty would be levied soon thereafter. Litigation is always a painful process of obtaining justice. It is not only a long drawn out process but also involves considerable time involvement and spending of large sums of money in terms of legal fees. In India, if any particular dispute has to go through the entire appellate and judicial process (starting with appeal to the CIT(A) and progressing all the way to the Supreme Court), then the entire journey would probably span anywhere between 1-3 decades depending on the complexity of the case and the pendency of appeals at various stages! One needs to be very patient if one decides to knock on the doors of justice. What makes matters worse is that in many cases, even after patiently pursuing the legal route and winning the case in the Supreme Court, ultimately the tax payer is not a winner. This happens when the Government amends the law with retrospective effect and overturns the court’s decision. This has happened in a number of cases and although most legal experts are unanimous in condemning such an action as being totally unconstitutional or unfair, it still continues to happen. Thus, to sum up, even small cases that result in a tax demand throw up a number of contentious and cumbersome issues for the tax payer. A large case like the Vodafone one is certain to create history in India in terms of the magnitude of the demand and the attention that the media has given to it. Of course, some of the issues referred to above may not apply to the Vodafone case since, as mentioned earlier, it is a matter relating to withholding of taxes and not a regular Scrutiny. |

|||||||||||||||

|

As soon as the application for keeping the demand in abeyance is received by the tax officer, invariably, the same is rejected. The tax payer is asked to pay the demand immediately. What follows is a round of negotiations leading to the tax payer having to plead with the higher officers (maybe even the Commissioner of Income-tax (CIT)). If the tax payer is lucky, the demand may be partly kept in abeyance. However, practically, experience shows that in almost every case, the tax payer is forced to pay at least 50% of the demand immediately and the balance may then be kept in abeyance for some period of time.

As soon as the application for keeping the demand in abeyance is received by the tax officer, invariably, the same is rejected. The tax payer is asked to pay the demand immediately. What follows is a round of negotiations leading to the tax payer having to plead with the higher officers (maybe even the Commissioner of Income-tax (CIT)). If the tax payer is lucky, the demand may be partly kept in abeyance. However, practically, experience shows that in almost every case, the tax payer is forced to pay at least 50% of the demand immediately and the balance may then be kept in abeyance for some period of time. Another fallout of a disallowance or addition being made in an assessment order is that it sets a precedent for subsequent years. In a large number of

cases, when a particular stand is taken by a tax officer, the same is mechanically followed in subsequent years by the same officer or his successors. This too causes severe problems for the tax payer as he is saddled with endless harassment in terms of recovery of demand, appeals, penalties and resultant litigation that goes on for years together.

Another fallout of a disallowance or addition being made in an assessment order is that it sets a precedent for subsequent years. In a large number of

cases, when a particular stand is taken by a tax officer, the same is mechanically followed in subsequent years by the same officer or his successors. This too causes severe problems for the tax payer as he is saddled with endless harassment in terms of recovery of demand, appeals, penalties and resultant litigation that goes on for years together.